Publicat a Diari la Veu

Últimament, he sentit sovint crítiques als partits de dretes que estan treballant per exterminar el valencià. Són crítiques legítimes i fonamentades. No hi ha dubte que ho volen fer. És important, però, que no ens deixem distraure; un error que, històricament, hem comés sovint els valencianistes. L’atac no ve de l’extrema dreta ni de la dreta. L’atac ve del nacionalisme espanyol, entés de l’única manera en què els partits espanyols l’entenen: el pancastellanisme.

L’equiparació d’estat i llengua i la idea que només el castellà està legitimat per a servir com a llengua de comunicació, han dominat el marc conceptual de tots els partits polítics espanyols; una idea plenament refrendada per la sacralitzada carta magna, que dona un suport inequívoc a la supremacia del castellà i —per tant— dels castellans.

El pancastellanisme és la idea que tot ha de ser en castellà, perquè malgrat el reconeixement constitucional d’autonomies o llengües, l’única manera acceptable de ser espanyol és ser castellà. Castellà de primera si el castellà és la teua llengua d’identificació i de comunicació, o ciutadà de segona si la llengua dels teus ancestres no és la de l’imperi, sinó alguna altra que —ràpidament— qualificaran de dialecte.

Alguns partits, com ara Vox, accepten plenament el pancastellanisme, en fons i forma. Uns altres el disfressen una miqueta per tal de fer-lo més passador, però tots el prenen com a premissa bàsica: es pot parlar de tot i a tothom en castellà; en les altres llengües, només es poden dir algunes coses i només a algunes persones, sempre que no hi haja present cap ésser superior (castellà) que podria arribar a sentir-se ofés.

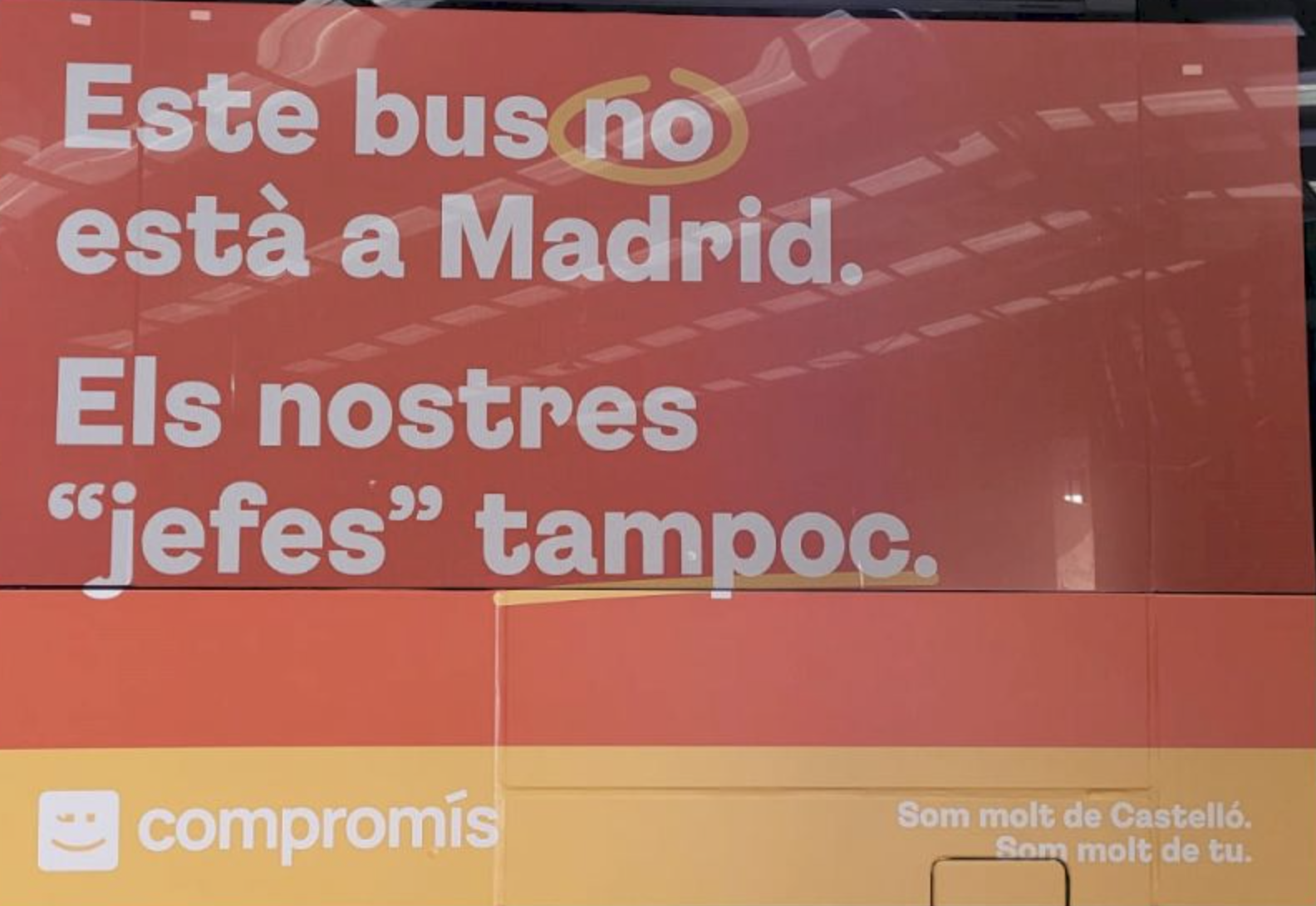

No ens xoca això quan ho fa Vox o el PP. Tampoc quan ho fa el PSOE (recordeu el president Ximo Puig parlant en castellà a Elx, amb ocasió de la celebració del Misteri), que d’ençà dels seus inicis ha abraçat el nacionalisme espanyol, només amb la dissimulació mínima quan els convé, com ara en algunes campanyes electorals. Ara ja ens hem acostumat també a vore-ho en Compromís, que com més va més gasta el castellà, com correspon a qualsevol partit de l’esquerra espanyola.

Ja vàrem vore com Baldoví se subordinava públicament a un adolescent madrileny, per a explicar-li —en perfecte madrileny— com funcionava el Metro de València (https://www.tiktok.com/@joan_baldovi/video/7212628835588640006) El candidat a presidir la Generalitat valenciana no té cap inconvenient en amagar el valencià quan el partit considera que això convé. També vàrem assistir a l’espectacle de l’anterior síndica del grup parlamentari, Papi Robles, responent en castellà a qui se li adreçava en la llengua de l’imperi, tal com ho farien María José Català, Manolo Mata o qualsevol dels altres representants de l’espanyolisme a les corts valencianes. O a la vergonyosa actuació d’Àgueda Micó intervenint en castellà a les corts espanyoles, fins i tot quan s’ha aprovat l’opció de parlar en valencià. El missatge és ben clar: davant dels amos, t’agenolles i parles castellà. Si algú pensa que això és el comportament d’un líder, deu ser perquè no en deu haver vist cap, de líder, en tota sa vida.

Ignore quins poden ser els càlculs electorals erudits, que els cervells brillants de Compromís han entrevist per a incorporar el pancastellanisme al quefer polític del partit. Potser han arribat a la conclusió que colliran més vots com a apèndix regional de l’espanyolisme d’esquerres, que no defensant els interessos valencians. I, per a ells, no hi ha cap argument més elevat que la caça del vot, al preu que siga: si cal sacrificar el país per a assegurar les poltrones, se sacrifica el país i au! El cas és que la incursió castellanista no és flor d’un dia. Ara, la mateixa Papi Robles, esta vegada en clau municipal del cap i casal, dobla l’aposta en una piulada (https://x.com/papirusa/status/1746143126404702574?s=20) en què se supera i pren la iniciativa per a adreçar-se directament en castellà als valencians, sense necessitat que ningú li ho impose; ni tan sols que li ho demane. Ja no cal, se subordinen per iniciativa pròpia per a deixar ben clara la vocació d’esclaus que els guia.

Deixem d’enganyar-nos: l’amenaça no ve de la dreta, ve del pancastellanisme transversal que es practica en tot l’espectre polític, de Vox a Podemos/Sumar/Compromís, passant pel PP i el PSOE, sense que n’hi haja ja cap excepció en tot l’àmbit parlamentari. No seria difícil concloure que els valencians necessitem un partit valencianista. Un partit capaç de prioritzar els interessos del país per damunt de qualsevol altra temàtica i —sobretot— per damunt de les ambicions individuals dels personatges mediocres que han ocupat les posicions de preeminència en un partit sense nord i sense principis. Un partit format per gent que no s’avergonyisquen de ser valencians, que no amaguen la llengua com si fora una cosa bruta i miserable. Gent que tinga la dignitat suficient per a dir qui són i qui som, per damunt de l’omnipresent electoralisme mesquí, que no té més horitzó que el dels seus culs sòlidament instal·lats a les poltrones que cobegen. L’espai polític del valencianisme ha quedat lliure per deserció manifesta dels anteriors ocupants. Algú hauria d’ocupar-lo.